- Home

- Tove Alsterdal

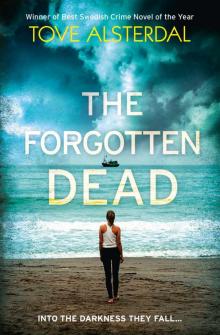

The Forgotten Dead Page 6

The Forgotten Dead Read online

Page 6

He shuffled all the papers into a neat little stack. Terese looked down at her hands. She could feel his eyes on her. Her bottom felt sweaty against the plastic of the chair.

‘And you didn’t see anything else on the beach?’ he asked.

She shook her head. ‘It was totally deserted. Nothing but a few seagulls.’

The officer turned to Stefan. ‘If she saw anything that might lead us to the smugglers, we want to know about it. These are criminals we’re talking about here.’

Stefan turned to Terese. ‘So you really didn’t see anything? No boats? No people?’

She shook her head as she spun the ring she was wearing. It was gold, in the shape of a heart. A confirmation present from her father.

‘Then all we need to do is write up your statement,’ said the officer. He pressed a button on his desk and a buzzer sounded outside the door.

‘My assistant will take care of it. We’ll want the precise time and where the victim was found.’

He narrowed his eyes and leaned across his desk.

‘And I also want the name of the person you were with. Or maybe there was more than one.’ His gaze slid over Terese’s body. She shuddered, thinking that she would need to take another shower when she got back to the hotel. That was how he made her feel. Dirty.

‘Did you get paid for it, or do you let them do it for free?’ he said.

At that point her father finally stood up and slammed his hand on the desk. ‘Enough. Stop harassing my daughter. She’s told you everything she knows.’

The door opened and another police officer came into the room. Terese recognized him. He was the one who had shown them in when they arrived. He looked nice. She got up and turned, about to leave.

‘We also need to report that your passport was stolen,’ said Stefan.

‘No, don’t, Papa,’ said Terese, taking him by the arm, but it was too late. He had already started talking to the officer about her missing passport.

‘Are you telling me it was stolen on the beach? But she said there wasn’t anyone else there. That doesn’t make sense. I don’t understand.’ The officer smiled broadly, the gap in his teeth like a black hole in his mouth. ‘So which of them do you think took your passport? Or was it a form of payment?’

His gaze settled on her body, as if licking her up and down, and then back up again to force its way between her breasts.

Terese squirmed and tugged at her father’s arm. She hated her arse and thighs, which were too fat, and her nose, which bent slightly in the middle. But her breasts were perfect. Round and naturally big. The only part of her body she was completely satisfied with.

‘I probably just dropped it somewhere,’ she said. ‘Come on, Papa, let’s go.’

‘No matter what, we need to file a report,’ said her father without budging.

‘For that, you’ll need to talk to the local police.’

‘We have to talk to the local police,’ Stefan Wallner translated for Terese, but she was already on her way out of the door.

‘I want to go home,’ she said when they were out in the corridor.

‘But we have a whole week left of our holiday.’

‘Didn’t you see how he was staring at me? He’s bloody disgusting.’

Her father looked over his shoulder at the door that had closed behind them. The officer’s assistant stood next to them, shifting from one foot to the other, holding the official form in his hand.

‘Somebody like that should be reported,’ said Stefan, putting a protective arm around his daughter. ‘Come on, sweetie, let’s get this over with. Then we’ll go out and have a really good lunch. Just you and me.’ He gave her a poke in the side. ‘And we’ll sit in the sun and have a glass of white wine. I think we need it. Both of us do.’

Chapter 4

Paris

Wednesday, 24 September

With a shiver of anticipation, I turned the key in the lock of room 43. As if he would just be sitting there. And he’d get up and come towards me with open arms and a look of surprise, wondering what I was doing here, laughing at me. What an impulsive thing to do, flying to Paris.

But all I found was emptiness. And the faint scent of lavender soap.

The door closed behind me with a muted click. Eight days and eight nights had passed. All traces had been carefully cleaned away.

I threw open the window. A damp gust of wind against my face. Beyond the rooftops rose the dome of the Panthéon. In front of me the university buildings were spread over several blocks.

It was here that Patrick had stood when he had called, in this very spot. I remembered his voice on the phone. I miss you so much … I’m headed straight into the darkness …

The wind was fluttering the curtains, which billowed up and then sank back to the floor. I turned around and took in all the details. The big bed, the open-work white coverlet with a floral pattern. On the wall, a framed poster of a sidewalk café. The telephone on the nightstand. That was the phone I’d heard ringing in the background. Someone had called to tell Patrick that something was on fire. But tell me what’s going on, in God’s name!

The room was exactly four metres wide and five metres long. After all my years as a set designer, I automatically took measurements. Four times five metres, twenty square metres. Those were the physical dimensions of loss.

In the corner of the far wall stood a small desk. That’s where he had sat to write, bending low over his computer. Patrick always sat that way, as if he wanted to smell the keyboard, breathe in the words. In reality he needed glasses, but he was too vain to get them.

In the bathroom I met my own face in the mirror. Pale, with blue shadows under my eyes. My skin creased with fatigue. I rinsed my face with ice-cold water. Splashed water under my arms, and rubbed my skin hard with a towel.

Then I got clean clothes out of my suitcase. I was going to turn over every single stone in this city if that’s what it took.

The price of a slave. That’s what it said at the top of one page. Followed by numbers, amounts that appeared to be sample calculations:

$90 - $1,000 (= $38,000 = 4,000 for the price of one.)

Mark up = 800% profit = 5%

30 million – 12 million / 400 = 30,000 per year. Total?

The last calculation had been crossed out. Next to it were also a few words scrawled across the page, underlined and circled:

Small investment – lifelong investment

The boats!

I kept paging through Patrick’s notebook, which was filled with these truncated and basically incomprehensible scribblings. I was sitting upstairs in a Starbucks café, determined not to leave the table until I’d figured out at least some of these notes.

The café was three blocks from the hotel, on a wide boulevard lined with leafy trees, and newsstands that belonged in an old movie. Everything reinforced by a feeling of unreality. Jetlag was making me hover somewhere above myself.

The simplest thing, of course, would have been to go straight to the police and report him missing. But Patrick didn’t trust the police. He would hate me if they came barging into his story. First I needed at least to find out what he was working on.

I ate the last bite of my chicken wrap and crumpled up the plastic. Then turned to look at his last note. That was how I usually approached a new play, by starting at the end — Where is it all heading? How does it end?

Patrick had jotted down a phone number. That was the very last thing he had written.

Above the number was a name: Josef K.

This is the endpoint, the turning point, I thought. After this he’d chosen to check out of the hotel, and he’d put this notebook in an envelope and sent it to me.

Keep this at the theatre.

I turned the page to the previous note. It was scrawled across the page, as if he’d been in a hurry: M aux puces, Clignancourt, Jean-Henri Fabre, the last stall — bags! Ask for Luc.

I spread the map open on the table. Looked up the words in the index of my guidebook.

Bingo! My heart skipped a beat. It was like solving a puzzle, and suddenly the answer appears.

I felt like I was on his trail.

Porte de Clignancourt was way up in the north, where the Paris city limits ended and the suburbs began. It was the end station for the number 4 Métro line. It was also the location of the world’s biggest flea market, Marché aux Puces. Rue Jean-Henri Fabre was one of the streets in the market. Then I read the next line in the guidebook and my mood sank. The market was open only Saturday to Monday. Today was Wednesday.

Out of the window I could look straight into the crowns of the trees. The leaves had started to fade, turning a pale yellow. At least it was easier working here than at the hotel. Patrick’s absence wasn’t screaming at me in the same way.

I continued paging through the notebook, studying what he’d written. There were a lot of names, addresses, and phone numbers, but no explanation as to who the people might be. I marked the addresses, one after the other, on the map, and slowly a pattern emerged, an aerial view of Patrick’s movements around the city.

When I looked up again, rain had begun to streak the windowpane, and people down on the street were opening their umbrellas. It was close to three in the afternoon, morning in New York. I massaged the back of my neck, which felt stiff and tight after spending the night in an aeroplane seat.

I got out my cell and started with the number on the very last page of the notebook. Later, when the rain stopped, I would go to see the places marked on the map. Force my body into this upside-down day and night, not wanting to waste any time.

The call went through. I glanced at the name: Josef K. Two ringtones. Three. A girl was wiping off the nearby table. A couple of tourists were talking loudly in Italian.

Then I heard a click on the phone, but no voice answered. The line was simply open, and I could hear the sound of traffic, a siren far away.

‘Hello?’ I said quietly. ‘Is there someone there named Josef? Hello?’

I was positive I could hear someone breathing.

‘I’m actually looking for Patrick Cornwall, and I wonder if you could help me. I’m in Paris, and I think he called this number and—’

The traffic noise stopped. Whoever it was had ended the call.

With a tight grip on my cell, I moved on to the next number on the list.

After four attempts to speak to someone, I gave up. The most extensive answer I’d heard was ‘no English’ and ‘no, no, no’.

I was seized with longing to call Benji instead. To hear how the opening night had gone. And whether Duncan had won the acclaim he’d wanted. But all of that seemed so distant, as if it had ceased to exist the moment I boarded the plane.

Benji was the only one who knew that I’d gone to Paris. I’d told him at lunch, when we were sitting on the steps of the loading dock on 19th Street, eating burritos with jalapeños from the deli across the street.

‘You’re out of your mind. I can’t handle everything on my own,’ said Benji, missing his mouth. A big dollop of meat fell onto his lap, along with some melted cheese and a limp slice of tomato. ‘What if something happens? What do I do then?’ He tried to rub the spot off his baggy designer jeans.

‘Nothing’s going to happen,’ I said. ‘The stage set is all done, and they’re going to dance this same performance for three weeks. I’ll be back long before then.’ I stuffed my half-eaten burrito into the empty juice container and stood up.

‘If anyone asks,’ I said, ‘just say that something has come up in my family, and I’m terribly sorry, et cetera. That’s all anyone needs to know.’

An hour before the curtain-up, I left the theatre. By then all the paperwork was in order: the account books and the certificate from the fire department inspection, the list of props that had to be returned — all in neat folders. Like a final accounting of that part of my life.

‘Kiss Patrick when you see him,’ said Benji, giving me a hug. I pulled away and didn’t reply, just waved as I ran out to the cab that would take me to Newark and the Air India flight to Paris, leaving at 21.05.

The pill was supposed to be taken no later than an hour before departure, but I’d sat with the blister pack of pills in my hand until the gate was ready for boarding. There was no way I was going to allow myself to be carried through the air in a closed tube without some sedative inside my body. I’d suffered from claustrophobia as long as I could remember, and it wasn’t just rooms with the door closed, basement apartments, and elevators. Sitting captive in an aeroplane or a subway was even worse. It was impossible to escape. There was no way out. I was at the mercy of other people, with no power over my own fate. That was probably why I became a set designer. In the theatre I built my own rooms and decided where the exits would be. Usually I was able to deal with my claustrophobia. I always checked to see where the emergency exit was when I entered a building, and I never rode the subway. If I needed to travel any distance, I hired a car. Going back to Europe had never been part of my plans.

I read the warning label over and over. If pregnant, consult your doctor, it said. And ‘there is a risk the foetus may be affected’. Forgive me, I thought as I swallowed the pill. Forgive me, but I have to do this.

The cab crept along the glittery Champs-Élysées and turned off right before the Arc de Triomphe. That’s where all the hustle and bustle ended. Rue Lamennais was lined with businesses, and most of the employees seemed to have gone home for the day. I asked the cab driver to pull over before we reached number 15, which was one of the addresses in Patrick’s notebook.

I stopped twenty metres away, ducking into the shadow of a doorway. A car slowly passed and slid to a halt in front of the entrance. Then another equally shiny vehicle arrived. The first was a Bentley, the second a Rolls Royce. Three men wearing dark suits came out of the building carrying briefcases. A doorman hurried forward to open the car doors, bowing and anticipating every step the men took in an obsequious dance. There was even a red carpet on the pavement. The cars started up and disappeared.

This was the second address I’d gone to see. The first had turned out to be an American bookshop. Typical Patrick. He loved to ferret out old editions of classic novels that cost a tenth of the price in paperback. I’d roamed around inside among millions of dusty books, up and down narrow stairways, past benches with cushions and blankets squeezed in between the aisles. When I sat down to take a brief rest, two hikers with backpacks came over to ask me if I was an author. ‘We’re authors too,’ said the boy. ‘But we publish our writing on the Internet. We think of ourselves as akin to the beat generation, but in a whole different context, of course.’

It was now six thirty, and dusk was hovering like a blue note in the air. Yet another shiny car glided past, this one a Jaguar. At that moment my cell rang in my shoulder bag. The doorman glanced in my direction. I looked at the display. Unknown caller.

‘Ally,’ I said.

‘You called?’ said a woman with a French accent. ‘You’re looking for Patrick Cornwall?’

Adrenaline coursed through my body. My knees felt weak.

‘Do you know where he is?’ I said. ‘I need to get hold of him.’

A brief pause on the line. No background noise.

‘We can’t talk on the phone,’ said the woman. ‘Where are you right now?’

‘On a street called rue Lamennais,’ I said. ‘Outside a restaurant.’ I quickly moved closer so I could read the gold script on the visor of the doorman’s cap.

‘Taillevent,’ I said.

‘In the eighth?’ said the woman.

‘Excuse me?’ I asked, thinking instantly of the baby. The eighth sounded like a month at the end of the pregnancy. ‘What do you mean?’

‘The eighth arrondissement,’ she said. ‘In half an hour. How will I recognize you?’

‘I’m wearing a red jacket,’ I said, and then she clicked off. I lowered my hand holding the cell and smiled at the doorman.

He smiled back.

‘Good news?’ he

asked.

‘I think so,’ I said, and put my phone away in my bag, going over the conversation in my mind. Thinking about the tone of the woman’s voice. Formal but not hostile. I strained to remember the fruitless phone calls I’d made earlier in the afternoon, but they all merged into one. It didn’t matter. I’d soon find out.

I smiled at the doorman again.

‘Is it possible to get a table for dinner?’ I asked.

The doorman surveyed my clothes: jeans and the red anorak I’d found in the Salvation Army shop on 8th Avenue.

‘I’m sorry but we’re fully booked this evening.’

He moved away to open the door of the next car that had pulled in, and I took the opportunity to slip into the restaurant behind him.

Thick carpets muffled all sound inside. The entire foyer was done in beige and brown. It looked like the decor hadn’t undergone any changes in the past fifty years. A staircase with an elaborate, gilded wrought-iron banister led up to the next floor. The maître d’ blocked my way.

‘Excuse me, I don’t speak French,’ I said, ‘but I’d like to ask you about a customer. I think he was here a little over a week ago, and—’

‘We do not give out information about our customers,’ said the man. ‘They rely on our discretion.’

‘Of course. I understand that,’ I said, smiling at him as I swiftly searched for a suitable lie, a role to play. I knew that Patrick would never go to a place like this merely to have dinner. He must have been meeting someone here, someone he was going to interview.

‘This is so embarrassing,’ I said, making my voice sultry and feminine. ‘I represent a big American company in Paris, and one of our business partners has booked a table here, and I’ve had so much going on, my mother died recently, and now I’m afraid that I’ve mixed up the days and the weeks.’

The maître d’ frowned and glanced around nervously. Two men in grey suits stood near the cloakroom, leaning close as they talked. A petite, energetic woman with a pageboy hairstyle briskly took their overcoats and hung them up.

‘So if you wouldn’t mind just checking to see which day he booked a table …’ I put my hand on the maître d’s arm. ‘I’ll be fired, you see, if I lose this contract.’

The Forgotten Dead

The Forgotten Dead