- Home

- Tove Alsterdal

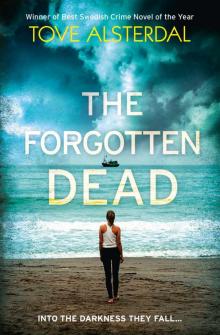

The Forgotten Dead

The Forgotten Dead Read online

Translated from the Swedish by Tiina Nunnally

Copyright

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollinsPublishers 2017

Copyright © Tove Alsterdal, 2009 By agreement with Grand Agency

Translation copyright © Tiina Nunnally 2016

Cover design by Alex Allden © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2017

Cover photographs © Max Bailen/Cultura RM/ Alamy Stock Photo (woman on beach); Shutterstock.com all other images.

Tove Alsterdal asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

Originally published in 2009 by Lind & Co, Sweden, as Kvinnorna på stranden

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008158989

Ebook Edition © August 2017 ISBN: 9780008158996

Version: 2017-05-22

Table of Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Acknowledgements

About the Author

About the Publisher

Chapter 1

Tarifa

Monday, 22 September

3.34 a.m.

The boat heeled over and the view through the small porthole changed. For a long while she could see only the masts of other boats and clouds, but now she glimpsed the town for a moment. All the windows were dark. If she waited any longer it would soon be dawn.

When she stood up a sharp pain shot through her left leg. The world swayed, or maybe it was the sea and the boat.

Before the man took off he had told her three or four o’clock. She had crept into the corner and sat as still as she could. ‘A las tres, cuatro,’ he said. ‘Esta noche,’ and she understood at last when he held up three, then four fingers and pointed at the sun, motioning that it was setting. Darkness. Night. That’s when she would leave. Tonight.

She couldn’t tell him that she had lost both her watch and her sense of time. That’s what happened when you prepared yourself to die and sank down into the big black deep where time no longer existed.

He had left a rolled-up rug on the floor of the cabin. She didn’t know what a rug was doing on a fishing boat. It was red, and woven in a beautiful pattern; it belonged on a tiled floor in an elegant room. If they have rugs like this in their boats, she thought as she unrolled it and curled up to wait, then I wonder what kind they have in their homes.

All sounds had ceased after that. The clatter of iron tossed onto asphalt, men’s voices, cars that started up and drove off. As the sun set the clouds turned a pale pink until all the colours vanished and the sky looked black and heavy. No moon, no stars, not a single fixed point. Like a silent prayer, a certainty that the world remained the same.

Slowly she pressed down the handle on the steel door. The smell of gasoline and the sea washed over her. She stepped quickly over the high threshold, closed the door behind her, and huddled on the boat’s deck.

The darkness she’d been waiting for had not arrived. The harbour was bathed in the yellow of sodium lights that were taller than church towers. She crouched there quietly and listened. A mooring line creaked when the boat moved. The rattle of a chain, the water sloshing gently against the quay. And the wind. Natural night-time sounds. That was all.

She grabbed the mooring line and slowly, very slowly, pulled the boat closer to the quay. With a dull thud the boat made contact.

She felt the rough surface of stone against her palms. Dry land. With her uninjured leg she kicked off and heaved herself up onto the dock. She rolled over and landed on her stomach behind a pile of rolled-up fishing nets. When she looked along the quay she saw a similar net with a rug covering it. So that’s what the fisherman uses those rugs for, she thought, to protect his nets from the rain and wind, or from animals that roam about, looking for fish scraps.

A few seconds passed, or maybe it was minutes. Everything was quiet, except for the wind and the beam pulsating on and off from the lighthouse.

She took a deep breath and then ran, stooping forward, moving as fast as her injured leg would allow, past a harbour warehouse. With his finger the man had drawn on the floor the way she should follow the wall out of the harbour, continue along the shore, and then go up through the town. To the bus station. From there she could catch a bus to Cádiz or Algeciras or Málaga. Cádiz was the name she recognized.

She stumbled over some pipes and heard the sound reverberate between the stone walls. Quickly she pressed herself close to a container.

There are guards, she thought as she listened intently. I can’t let myself be fooled by the calm and the quiet, and besides it isn’t really quiet. I can hear the surf striking the seawall, and the wind making the sheet metal clatter somewhere nearby, but I don’t hear any footsteps, and no one can hear mine.

She looked down at her bare feet. Her shoes had been swept out to sea, along with her skirt and cardigan. Now she was dressed in a green jacket that she’d found draped over her when she awoke on the deck of the fishing boat. In the cabin she’d found a towel and tied it around her hips as a skirt.

She pulled the cap further down over her forehead, climbed carefully over a pile of rebar. Hunched over, she ran the last bit before sinking onto a heap of empty plastic bottles bound for recycling.

This was where the harbour ended. She was hemmed in. In one direction was the high wall, in front of her a stone grate two metres high, and beyond that more harbour warehouses. She could see a section of street through the gaps, and some flowering weeds had pushed up through the holes in the asphalt. In the distance the ruin of a huge fortress loomed like a stone skeleton against the sky.

Her eyes hurt. She felt the strain of trying to focus in the yellow light, which was neither bright nor dim — more like a never-ending dusk. If she closed her eyes she would plunge into emptiness. It had been a long time since she’d slept a whole night through.

She got onto her knees and paused. That was something she’d learned in the past few months: to look all around, take notice of everything, and carefully plan her route.

Then she heard the sound. A vehicle approaching, inside the harbour area. She flattened herself against the ground and held her breath. The beams of the headlamps struck the wall right next to her feet. Bottles and oth

er rubbish glinted in the light. That was when she caught a glimpse of the stairs leading up over the wall, white steps carved into the stone only a few metres away. Then semi-darkness descended again. The vehicle had turned and was heading away. It hadn’t stopped. Thank God it hadn’t stopped. She saw the blue light on its roof before it vanished in the direction of the gates, and the noise of its engine died away. A police car.

She raced up the stone steps and scrambled over the wall. To her surprise she landed on something soft. So far everything she’d encountered in this country had been hard: asphalt, stone, and iron pipes. But now she had soft sand underfoot, and it was like being caressed by the ground.

An umbrella lay overturned on the beach. Just for a moment, she thought, I’ll take shelter, I’ll rest here for only one breath of God’s eternity.

She picked up a fistful of the fine sand and let it run through her fingers. Tilted her head back and looked straight up at the black sky. The wind blew into her face and tore off her cap.

When is this wind going to stop? she thought. When will the wind subside and the sea grow calm?

She stood up again and realized that her leg would no longer support her. Her foot felt like it wanted to leave her body, and she had to drag it behind her.

Crouching down she continued along another low wall that kept the sand from drifting across the road and turning the town into a desert. Sharp weeds cut her feet. She raised her bad foot to see if it was bleeding and discovered that she had stepped in dog shit. Her foot stank. She couldn’t make her appearance in this country with such a foul smell clinging to her foot, but it was too far to hobble down to the sea and rinse it off. What sort of person had she become? She rubbed her sole on the sand to get rid of the stink, then wiped away her tears with her hand and got sand in her eyes. The sand was everywhere.

I could walk along the road instead, she thought. Like a normal person, not like a thief or a dog afraid of being beaten. The road was lit, and she knew it was dangerous. Yet she straightened up and soon the asphalt of the road was beneath her feet. For a moment she felt like a human being again. Someone who walks without fear.

As if such women walk barefoot through town in the middle of the night, she thought. And just then she caught sight of something lying on a slab of concrete, a resting place by the road.

I’m hallucinating, she thought, I can no longer trust my eyes. She went closer and found that her eyes hadn’t deceived her. A pair of shoes. She reached out her hand, but hesitated and looked all around. Was it a trap? Was somebody trying to trick her? But who would think up such an odd idea?

It was nothing short of a miracle. A gift from God. She hesitantly touched the shoes lying there. They were real. And they were made of gold.

All right, she thought and picked them up. They were quite ordinary cloth shoes that had been dyed gold, but still. They almost fit. Just a little tight in the toes. She didn’t intend to complain. Some divine power had placed these shoes in her path. Wearing these shoes she wouldn’t have to step in dog shit.

For the first time since she had come ashore she turned around and gazed back. On the horizon, across the straits, Africa loomed like a gigantic shadow. How close it was. She could see the mountains and the scattered lights in the dark.

Then she walked on, and did not turn back again.

Please let this be a nightmare, thought Terese Wallner when she awoke, lying on the beach. Let me wake up again, but for real this time, and in my own bed.

Slowly she sat up, a terrible pounding inside her skull. The sea was in motion, darkly surging towards her. A flock of slumbering gulls stood in a pool left by the receding tide. Otherwise the shore was deserted.

She closed her eyes, then opened them again, trying to comprehend what had happened. There was nothing around her, that much was true. He was gone.

Her white capri trousers were filthy, and the sequinned camisole and cardigan offered no protection from the cold. The wind cut right through them. Her mouth was as dry as a desert and filled with sand. She spat, cleared her throat, and tried to rub away the sand with her fingers, but it had settled under her tongue and seeped way down her throat. She would need a giant bottle of water, at the very least, to rinse it all away. But where was her purse?

Terese dug her hands into the sand around her. It was hard to see in the dim light. A dark-greyish dusk intermittently pierced by flashes that hurt her eyes, coming from the lighthouse beam. She knew it was out there on an island. Isla de las Palomas, island of the doves. Off limits to tourists. A military area. Reached by a causeway, but with signs posted at the gates. The waves slammed against the rocks out there, spraying high into the air.

Then she caught sight of her purse, and her heart leaped. It was lying half-buried in the sand, less than a metre from the dent where her head had lain. She grabbed it. Everything was still inside: her wallet and hotel room key, her mobile and make-up bag, even her good-luck charm, which was a tiny frog on a keychain. And the bottle of water, thank God. She always carried water with her when she went out, since the tap water tasted so terrible in Spain. There was still a little left in the bottle. First she rinsed her mouth and spat out the water. Then she drank the rest of it, wishing there was much more. She picked up her wallet and opened it, her heart racing. The banknotes were gone. She’d had almost a hundred euros when she’d gone out for the evening. She couldn’t possibly have spent that much on drinks. What about her passport? She rummaged through her bag, but it wasn’t there. Terese was positive she’d brought her passport, as she always did, even though everyone said it wasn’t necessary.

Her shoes were also gone. She stared at her feet. They were suntanned, but white around the edges, with sand clinging between her toes. She looked all around, but the ballet flats she’d worn were nowhere to be seen. When had she taken them off? Before or after? She rubbed the palms of her hands against her forehead to stop the uproar inside.

I need to think clearly. I need to remember.

Had she been barefoot as she ran across the sand with him holding her hand, urging her down towards the sea, both of them laughing loudly into the wind, wondering if their laughter would be blown away?

She pictured his tousled, sun-bleached hair, his eyes gleaming as he looked at her. His arms were hard and sinewy, muscles taut from working out. His shirt fluttered open so she could see his brown abdomen, not a scrap of fat anywhere. She couldn’t believe she was the one he’d taken by the hand as they closed up the Blue Heaven Bar. He’d whispered in her ear that they should move on to someplace else. ‘You can’t go home yet,’ he’d said. ‘Not when I’ve just found you.’

Terese ran her hand lightly over the sand next to her. It was cold. Was there a slight indentation, an impression that his body had left behind, a trace of warmth? But that might simply be her imagination, because the wind blew more steadily in Tarifa than anywhere else on earth, wiping away all tracks in an instant.

No one needs to know what happened, she thought. Nothing did happen. Not if I don’t tell anyone.

She drew her cardigan tighter around her. Sand chafed inside her knickers. She felt sticky down there.

‘But what if someone’s here?’ she’d said as he urged her towards the sea. ‘What if someone’s here, watching us?’

‘You’re thinking about the wrong things,’ he said, kissing her, pressing his tongue deep inside her mouth. And his hands were everywhere, under her camisole and inside her knickers all at once. Then he unbuttoned her tight capris and slid them down and they tumbled onto the sand together. And she thought she might fall in love with him. She thought he was the most gorgeous guy she’d ever been with.

If only her friends could see her now!

You can’t go to Tarifa without having sex on the beach, he’d told her. It would be like not seeing the Eiffel Tower in Paris.

Then she’d felt the sand against her skin as he pressed her down. Grains of sand rose up between her buttocks and pushed between her legs as he guided his

cock with his hand, not finding his way at once, rooting around. All she felt was a scraping as he seemed to pump her full of sand.

She shouldn’t have fallen asleep afterwards. It had happened so fast.

From up in the mountains came the endless rumbling of the wind turbines, turning counter-clockwise. She had thought they looked like electric eggbeaters, whipping the air into cream. He laughed when she said that. Terese bit down on her fingertips to keep herself from crying.

He must have thought I was no good. Worthless. Otherwise he would have stayed and made love to me again and again.

Nausea rose up into her throat. She might have had two or three Cosmopolitans, and then a few Mojitos after that.

The whole beach swayed as she stood up. She leaned forward with her hands on her knees and stayed like that until things stopped moving, swallowing over and over to keep herself from throwing up and having to smell everything that spewed out of her. She couldn’t bear to be so disgusting. That was why she staggered down to the water. It wasn’t far, maybe twenty metres.

She moved slowly, setting her feet down carefully, so as not to step on anything unpleasant. The sand felt cold under her feet, and she was surprised when the first wave reached her. The water was almost lukewarm and silky smooth. She waded out a few steps to meet the next wave. When it broke, she caught the foamy water in her hands and splashed it over her face. It was refreshing and made her think a little more clearly.

To her left a low, black ridge rose from the sea, a jetty of large rocks that extended at least ten metres out into the water. It looked like a big prehistoric animal resting on the shoreline, the spine of a slumbering brontosaurus. She waded towards it, thinking that she would climb up and sit on the rocks at the very end. Let the sea wash over her wrists for a while. That usually helped against nausea. If she did throw up, the vomit would vanish into the water in seconds and be forgotten.

The Forgotten Dead

The Forgotten Dead